The “Connie Survivors” website’s log entry on the uncertain fate of the Lockheed Super Constellation registered as N6011C is about as basic as it gets: “Fuselage and engines noted in a scrap yard in Arica January 1996”. Despite the very limited report, that single sentence provided more than enough incentive for me to make the relatively short hop from my home in Santiago to Chile’s far north for an eyes-on update of the Connie’s status. Since my arrival in Chile in 2002, I’ve trekked to and documented a number of aviation crash sites in the central Andes, but this new type of search and the following account, took on a more meaningful purpose right from the start. Having no clear idea of how I’d track down the former Trans World Airlines propliner, on the morning of May 6th I boarded a northbound LanChile flight carrying a digital camera, a few photos of derelict Connies and a sense of curiosity that would’ve killed a dozen cats.

The town of Arica is located in Chile’s Region I, the country’s northernmost province, on a patch of sand situated along the western coastline of South America. Not much more than a gas-and-go stop on the way to Lima or La Paz, Arica’s Chacalutta (pronounced chak-eye-oo-tah) airport is laid out just 15 miles from the border with Peru and about a twenty-minute prop engine flight from Bolivian airspace. This remote location places Chacalutta at the near top of a long list of the dozens of known “secondary” airstrips used by the contraband-laden charters plying the South American skies in the late nineteen sixties. Christened the “Star of Missouri” by TWA in 1950, I now refer to her as the “Chacalluta Connie”, a good ol’ girl that ended up in a very bad way.

After the three-hour flight and a short taxi ride into town, I wandered into an Internet café and bicycle rental shop at the entrance to the old Arica – La Paz train station. I explained the purpose of my journey to the manager, Bernardo, and flipped though a few of the Connie photos. He paused for a moment and then asked to borrow my cellular phone. Another loco Norte Americano with an equally loco idea? I guess not. To my amazement, a fellow that I had only met a few minutes before dialed up his close friend who worked in the administrative division at Chacalutta airport. My search for a scrap yard, practically in the middle of nowhere, and the possibility of locating the muy famoso Constellation, seemed one step closer to bearing fruit. Carlos has been with the Chacalutta airport administration for a number of years and was understandably subdued about the gringo’s inquiry. Only after some coaxing on the part of Bernardo, was I able to jot down the “official” version of what occurred when N6011C touched down and rolled to its final powered stop in 1969.

According to Carlos, the Connie’s flight originated at a pista de aterrizaje alternative or alternative airstrip somewhere in Bolivia. It seems logical that a failure of one of its four Wright Cyclone 749 C18BD1 engines would jeopardize the crew’s hopes of safely navigating the central Andean mountains and the vast jungles to the north. Turning back towards its point of origin, N6011C’s banditos made the obvious choice and flew in the direction of the small airfield with its single strip of north/south asphalt. Carlos noted that immediately after engines-off (there were no flames visible on the failed engine), the crew abandoned the aircraft and disappeared on foot across the tarmac and into the sand in the direction of the Peruvian border. He also recalled that the carabineros, Chile’s version of a state police force, described the aircraft’s interior as being completely filled with wooden containers of various dimensions. When asked if he or anyone else knew what was in the containers, he replied that this information was “classified” and suggested that I contact the Dirección General de Aeronáutica Civil (DGAC) in Santiago if I wanted to know more. Several thousand miles from the U.S. and wearing a green and black livery, her captors considered the former “Star of Missouri” a contrabandista’s aircraft. Not pressing the issue any further, and to avoid ruffling local feathers along a trail that was 35 years long, I’d have to check elsewhere. As of this writing, the DGAC declines to disclose the full report of the “classified” aircraft incident investigation that remained active from 1969 until 1974. An article appearing in a Chilean newspaper several years ago made reference to the Chacalutta Constellation’s fate at auction in July of 1974 as being “…suspended to last hour by legal impediments related to its customs situation.”

Hector Sotomayor, the father of a Chilean-American friend of mine in Santiago, had previously agreed to act as driver, interpreter and ambassador of good will during my visit to Arica. We hooked up around one o’clock and in a few minutes the two of us were motoring to the first target junkyard or chatarra located on the outskirts of town. Finding a scrap yard in Arica, despite the featureless landscape and open areas, isn’t as easy as one might imagine. Misleading signs, 15-foot high concrete and sheet metal walls made the job troublesome at best. Check the Yellow Pages? Forget it, way too expensive for the local scrap moguls. And besides, everyone knows where everything is in Arica. Right? Wrong. Frustrated with directions that brought us to half-empty lots filled with rubbish and derelict automobiles, we stopped in front of a small metal shop specializing in aluminio. We walked over to the cinder block hut where the chain link fence curled back to form an entrance and asked the occupant if he had any information about a scrap yard that might have un aeroplano muy grande parked inside. The owner stepped right up and said he’d purchased several pieces of the airplane we were searching for in June of 2002. He volunteered to show us the pieces, and after clearing a few 55-gallon drums from in front of a locked sea container, I followed inside and watched as an assistant sorted through a pile of metal towards the rear of the dimly lit and dusty box. After two or three minutes of metal being tossed and banged around, there it was; the familiar form of an aircraft fuselage - zinc-chromate on the inside curve of a section of dulled aluminum. I took a couple of photos, backed out of the container and asked Hector to find out if the owner recalled where he bought the aluminum.

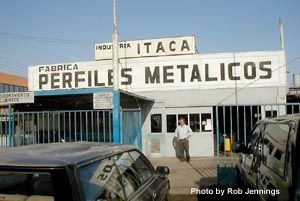

Thanking him for the directions to the ITACA metal company, el jefe’s directions had us bounding down the dusty road, congratulating each other on our fortunate stroke of luck. If this was good information, the “Star of Missouri”, or what was left of her, was just down the road. For sentimental reasons and admittedly against the odds, I silently hoped that the pieces of aluminum in the container might’ve come from a different aircraft, perhaps one of a less esteemed lineage than the venerable Lockheed Super Constellation.

Fernando Leyton has been with the ITACA Metal Works Company for over 18 years and is the chief of production for this outfit, located just off the paved road heading north out of town. His assistant and chief of sales, Mr. Fidel Castillo, has been with ITACA for over 39 years. They confirmed that the owners of ITACA, Antonio and Darko Dekovic had the pink slip to Lockheed’s c/n 2647. The Dekovic’s records indicate that payment for the Connie was made under check number 2798, for the amount of 7.14 million escudos, dated July 30, 1974 payable to the to the DGAC through the “Caja de Credito Popular” bank. The obsolete Chilean “escudo”, worthless in today’s economy, traded at 950 to one U.S. dollar on the date of purchase. For the modest sum of roughly $7,515.00, the Dekovics took final possession of Matricula N6011C – Serie 2647, Modelo Lockheed L-794-A-79.

Fernando Leyton has been with the ITACA Metal Works Company for over 18 years and is the chief of production for this outfit, located just off the paved road heading north out of town. His assistant and chief of sales, Mr. Fidel Castillo, has been with ITACA for over 39 years. They confirmed that the owners of ITACA, Antonio and Darko Dekovic had the pink slip to Lockheed’s c/n 2647. The Dekovic’s records indicate that payment for the Connie was made under check number 2798, for the amount of 7.14 million escudos, dated July 30, 1974 payable to the to the DGAC through the “Caja de Credito Popular” bank. The obsolete Chilean “escudo”, worthless in today’s economy, traded at 950 to one U.S. dollar on the date of purchase. For the modest sum of roughly $7,515.00, the Dekovics took final possession of Matricula N6011C – Serie 2647, Modelo Lockheed L-794-A-79.

To move the aircraft from the airport by tow truck, the ITACA crew welded cable attachment plates to the landing gear struts, removed all four engines and cut most of the wings away to lighten the airframe for the four kilometer trip to the yard. Today, segments of both main wings, landing gear with their hardened Firestone tires, the mostly complete nose

wheel assembly, eight cut away props, a couple of pumps and a few filters remain neatly arranged in the open yard behind the main work shop. When I climbed down from taking my third or fourth close up photo of a pump bearing TWA part number tags, Fernando asked me if I’d be interested in seeing the equipment he had stored inside the workshop. He only had to ask once. Opening a locked storeroom, I was surrounded by 8-foot high shelves overflowing with cables and

pulleys, wiring, nav and radio parts, antennas, a de-icing control panel, and hundreds of other bits and pieces archived by the Dekovic brothers. I felt like an archeologist that had stumbled upon an ancient crypt loaded with treasure. Photos only, no mementos. The brother’s prize piece must certainly be the Bendix radar antenna sitting alone on a top shelf in the main machine shop. I lifted back the plastic sheet to get a good shot of the round antenna. It appeared to be in mint, NOS condition.

Before I left the scrap yard, Fernando handed me a neatly cut 4” by 2” piece of aluminum with the faint red letters “…ALCL…” marked on the primer side of the small relic. I’ll frame it nicely, and gladly tell all that will listen, why this innocuous looking piece of metal has a place of prominence in my den.

On a final note, three of N6011C’s four engines are airborne again, their history rekindled on another Connie in a place far from the northern deserts of Chile. I hope this narrative serves as a link to their heritage and the otherwise final accounting of another L749A. (Editors Note: Those engines are now installed on the Dutch Aviodrome’s L749A Connie N749NL)

Rob Jennings

May 2004

Photo Credits: Rob Jennings

Fernando Leyton has been with the ITACA Metal Works Company for over 18 years and is the chief of production for this outfit, located just off the paved road heading north out of town. His assistant and chief of sales, Mr. Fidel Castillo, has been with ITACA for over 39 years. They confirmed that the owners of ITACA, Antonio and Darko Dekovic had the pink slip to Lockheed’s c/n 2647. The Dekovic’s records indicate that payment for the Connie was made under check number 2798, for the amount of 7.14 million escudos, dated July 30, 1974 payable to the to the DGAC through the “Caja de Credito Popular” bank. The obsolete Chilean “escudo”, worthless in today’s economy, traded at 950 to one U.S. dollar on the date of purchase. For the modest sum of roughly $7,515.00, the Dekovics took final possession of Matricula N6011C – Serie 2647, Modelo Lockheed L-794-A-79.